The previous blog post presented a comic where the characters talk about ‘this’ and ‘that’ and ‘here’ and ‘there’ in Dieri. Here it is again:

Here is what the two characters are saying (Warrangantyu means ‘left, left-hand’ and is the character on the left, and Ngunyari means ‘right, right-hand’ and is the character on the right in each panel):

| Warrangantyu: |

minha nhawuwa? ‘What’s that?’ |

| Ngunyari: |

wirdirdi? nhingkirda? ‘Where? Here?’ |

|

| Warrangantyu: |

wata! nhawuparra nhingkiwa ‘No, that one, there’ |

| Ngunyari: |

nhaka? pirtanhi? ‘There? In the tree?’ |

|

| Warrangantyu: |

wata yaruka warritha marla ‘Not that far away’ |

| Ngunyari: |

aa nhingkiwa ‘Oh, there’ |

|

| Warrangantyu: |

kawu ‘Yes’ |

| Ngunyari: |

nhawuparramatha mutaka ngakarni ngapiraya ‘That’s my father’s car’ |

English has only two words ‘this’ and ‘that’ to talk about things, and ‘here’ and ‘there’ to talk about locations. Dieri has more terms and is able to make subtle contrasts that are lacking in English.

To point out something we can use the words nhani ‘she, this’ for females and nhawu ‘he, it, this’ for everything else (these are the forms we use for intransitive subject in Dieri — the full set of forms for other functions are listed in this blog post). We can then add to these words endings that show distance from the speaker and the person spoken to:

-rda ‘right next to the speaker’, around 1 metre away

-ya ‘near the speaker’, around 2-3 metres away

-wa ‘far from speaker’, over 5 metres away

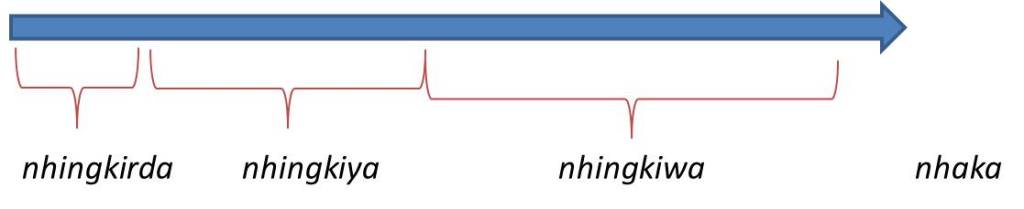

This gives us the following diagram:

Dieri has two other useful endings:

-parra ‘previously mentioned’, indicates something that the speaker or another person has mentioned previously, or that is being pointed to

-matha ‘identified information’, indicates that the speaker is able to identify the thing being spoken about

This gives us:

nhawuparra ‘this one we were talking about’

nhawumatha ‘this one that I just realised what it is’

You can combine these to give:

nhawuparramatha ‘this one that we were talking about that I just realised what it is’

This is used Ngunyari in the last frame when he realises exactly what it is that Warrangantyu has been pointing to all the time.

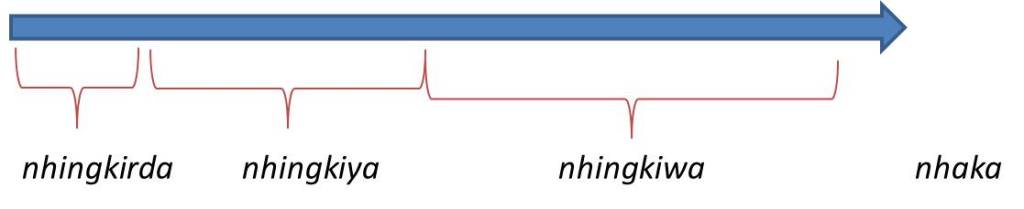

Finally, to talk about locations we have the following terms in Dieri (notice that English has only ‘here’ and ‘there’):

nhingkirda ‘here, right next to the speaker’, around 1 metre away

nhingkiya ‘here, near the speaker’, around 2-3 metres away

nhingkiwa ‘there, far from speaker’, over 5 metres away

nhaka ‘there, far from the speaker and the person spoken to’, a long distance away (including places that cannot be seen, like places over a hill or on the other side of the world)

This gives us:

Note: The two characters also use two very useful Dieri words kawu ‘yes’ and wata ‘no’ in their discussion.